BLACK HISTORY MONTH – UNLOCKING THE BARRIERS

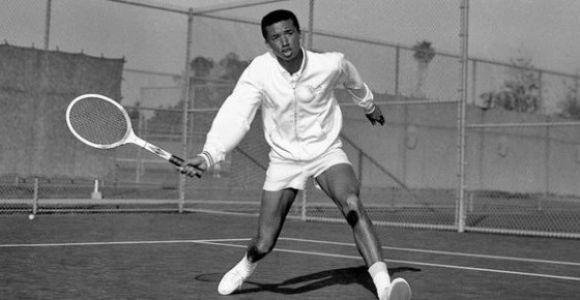

One Of Tennis Greatest Stars and Global Ambassador for Equality. Arthur Ashe At UCLA. Photo courtesy of UCLA.

By Mark Winters

In 1926, Carter Woodson, a historian and co-founder of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, came up with the idea of making the second week of February “Negro History Week”. The goal was to broaden understanding of historical issues and to provide cultural insight into those topics at a time when teaching Black History (which was the immediate goal of Negro Week) wasn’t well received.

Negro History Week was celebrated annually until 1969 when Black United Students at Kent State University proposed that Black History should be celebrated the entire month of February. A year later the first month-long commemoration was held at the university. In 1976, as a part of the US Bicentennial Celebration, Black History Month was officially recognized by the US government.

On November 30, 1916, the American Tennis Association (ATA) was founded which marked the beginning of the African-American game as we now know it. The Association Tennis Club of Washington, D.C., and the Monumental Tennis Club of Baltimore, Maryland, joined forces to respond to the United States Lawn Tennis Association’s policy of excluding players of color from participation in tournaments.

The inaugural ATA National Championships was held August 1917 at Druid Hill Park in Baltimore. Men’s and women’s singles, along with men’s doubles, were contested. Soon, racial separation policies made it necessary for the tournament to be staged at sites such as Central State, Lincoln, and Hampton Universities as well as Morehouse College in Atlanta. The African-American schools offered courts and housing accommodations. But, more important, the annual “coming together” became a social activity that was a highlight each year.

In those days, “East was East, and West was West”, and the difference between the two regions was more than simply a coastline. What is often overlooked is that because of the differences in attitudes toward race, players from the Los Angeles area established The Western Federation of Tennis Clubs (TWFTC) in 1916, the West Coast counterpart of the ATA.

The first meeting of the TWFTC took place at the Downtown YMCA in Los Angeles. Today, the organization is now known as the Pacific Coast Championship, Inc. and is made up of clubs ranging from San Diego to Sacramento.While the ATA has been at the forefront of opening tennis doors to African-American players, Southern California has played an essential part in the progress that has been made as well.

Looking back it is painfully ironic that in tennis history, little if any, mention is ever made of Howard and Tuskegee Universities offering students an opportunity to play tennis beginning in the 1890s. Another significant, but ignored, reality is that at the end of the decade – 1898 to be specific- African-American players from the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast were taking part in tournaments staged at the Chautauqua Tennis Club in Philadelphia.

Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe were tennis legends and icons. Before earning Grand Slam singles titles, though, they were ATA National champions. Gibson claimed a record ten straight singles titles, and Ashe was the singles winner from 1960-62.

Jimmie McDaniel grew up in Los Angeles. His tennis skills which he developed on the local public courts enabled him to become a tennis star at Xavier University of Louisiana – New Orleans. An ATA National champion from 1939-41, he broke the color barrier when he played Don Budge, who won the first Grand Slam in 1938. The exhibition match took place at the ATA-affiliated Cosmopolitan Tennis Club in Harlem on July 29, 1940, in front of 2,000 spectators. Budge, who turned professional after winning the Australian, French, Wimbledon and US Nationals, took the singles in straight sets. He then paired with Reginald Weir against McDaniel and Richard Cohen in a doubles contest. (Weir made history again in 1948 when he competed at the USLTA Indoor Championships in New York.)

When she was in her nineties, Jean (nee Glover) Richardson, a Los Angeles resident, recalled driving to the ATA National Championships. She regularly traveled with Eleese Thornton, Bertha Hancox and Myrona (Roni) White. Richardson remembered playing Althea Gibson for the first time at the ATA Championships at Bethune-Cookman College (now University) in Daytona Beach, Florida. She faced Gibson again at Wilberforce University in Ohio, which is the oldest private African-American school in the US. She also recalled seeing Arthur Ashe, as a twelve-year-old, play at that Florida event.

As a junior player, Beverly Coleman was touted as the “next Althea”. She fondly reminisced about the help Jean Richardson provided and how one year she rode with Eleese Thornton to the ATA National Championships. They were joined by Earthna Jacquet, (the 1954 singles winner) and Willis Fennell, a twelve-year-old with huge potential.

Coleman was fifteen at the time and reached the Girls’ final. She remembered that Jacquet, a superb serve and volleyer, did much of the “heavy driving”. Extremely handsome, he not only hit with her, in Los Angeles when she was a teenager he also made sure she was always safe, no matter the situation. To this day, Jacquet, who is revered locally, is still taking care of youngsters who need guidance, whether in tennis or life in general. He is renowned for helping those who don’t have fathers and has even secured scholarships for a group of Los Angeles boys enabling them to attend Morehouse College, where he still has contacts.

Black History Month is always much more than the second month of the year. This is particularly true in 2018. Tennis and those who are passionate about it have an opportunity to make a difference for more than the game. If tennis is truly the sport of a lifetime, it is essential that barriers are padlocked and those who cherish what it offers have the keys. Exclusions don’t define a sport. Side-by-side, everyone can make a difference.

Henry Talbert. Also a former UCLA Bruin • Henry was a dedicated friend of tennis. He spent his life growing the sport. He was Director of Southern California Tennis Association. Henry passed a few years back. 10sBalls had awarded him the “Gussy Moran” Humanitarian Award handed to him by Novak Djokovic.

Photo of Mark Winters. A Tennis journalist known worldwide for decades as a historian and a man of integrity. A standout player at UCLA and a true friend of tennis.

Topics: 10sballs, Althea Gibson, Arthur Ashe, Black History Month, Mark Winters, Tennis

10sBalls Top Stories

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Casibom: Yaşayan Casinolar ve Bahisler Lider Platform

- Sea Star Casino: Play Games Without Registering Online

- JETZT DEN SWEET BONANZA SLOT GRATIS DREHEN

- Азартные игры с Мостбет Казино – испытайте удачу

- Çevrimiçi en iyi yuvalar: Hizmetinizde Karavan Bet Casino

- Top No Deposit Free Spins Offer for Canadians – December 2024

- Abe Bet Casino: Ücretsiz dönüşlerle heyecan hissedin

- Ünlü slotlar çevrimiçi kumarhanelerde başarı bet giriş ücretli formatta

- BasariBet Casino Giriş – En Güzel Canlı Casino Oyunlarına Katılın

- Игра на деньги в казино 1вин казино: безопасность

- De parking de credits sans oublier les Diction Casino Archive sauf que Perception

- Играть в хитовые слоты в надежных клубах azino777

BLACK HISTORY MONTH – UNLOCKING THE BARRIERS |

BLACK HISTORY MONTH – UNLOCKING THE BARRIERS |