Lew Hoad Profile by Richard Evans

To find the great lion in his lair towards the end of a memorable life, you needed to take the coast road from the Lew Hoad Campo de Tenis near Mijas through the glitz of Marbella and then turn right at Sotogrande. The road took you past the Valderrama Golf Club and up into the hills of Andalucia; through cork and olive trees; past the herd of bulls where a Ferdinand was always munching away in the shade and then, finally make a final turn as the fortress of Castellar de le Frontera became emblazoned against the sky line.

Walking through the arch of what was once the palace of a 14th century Moorish King, you would find the white façade of a little town house and, just maybe, the owner, clad in crumpled white tennis shorts and an old T-shirt, sweeping leaves off his front steps.

“Want a beer, mate?” the eyes would crinkle around the edges in a welcoming smile. The next few hours, in the company of Jenny who taught him so much about the finer things in life, would be taken up with tennis tales and the local gossip from this little walled village that contained seventy tiny houses in varying states of repair.

For several years in the 1980’s and 90’s in between travels, I was Lew and Jenny Hoad’s immediate neighbor in the plaza and they were special times. I had first heard about this extraordinary place, which offers sweeping views over Gibraltar all the way to the Riff Mountains in Morocco, when the Hoads and I were invited to the Paris home of Aimé Maeght, a famous art dealer.

Standing on the balcony, Lew said, “I think I’ve blown my last peseta but I just couldn’t resist this place we just bought. It’s bloody marvelous.”

So a few months later they drove me up there and Lew was right. In many senses, Castellar is out of this world.

So we’re talking art and architecture and all things Spanish – not subjects that some people would expect when discussing the life of a rough, tough Aussie tennis champ who burst out of a modest Sydney home, looking like a Greek god and playing tennis that myths are made of.

Until Roger Federer came along, I thought Lew Hoad was the greatest tennis player in the world. And I was not alone. In his book “Ahead of the Game”, Owen Williams the great South African promoter who played on the amateur circuit when Hoad was winning his Grand Slam titles, tells of how his colleagues on the tour used to sit around over a drink trying to decide which player they would want to play for their life.

“There were a few good candidates,” Williams told me. “But in the end it always came down to Hoady. Providing, of course, that his back wasn’t too bad and he was relatively sober!”

And then there was Pancho Gonzalez, his greatest rival on the pro tour, who, as he mellowed into late middle age, admitted that Hoad was the only player he really respected.

So was it the chronic back in jury; his somewhat laconic, laid-back attitude to winning tennis matches or Ken Rosewall, his ‘twin’ of teenage years, that prevented Hoad from achieving the Grand Slam and etching his name more deeply into the history of the game than is currently the case? Probably all three.

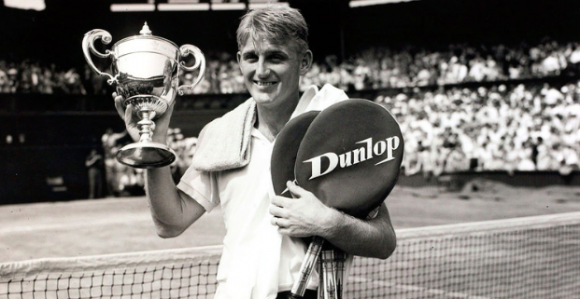

The back became a continuous problem almost as soon as he turned pro in 1957, having won his second Wimbledon with a crushing defeat of the next year’s champion, Ashley Cooper. But in 1956, it appeared that nothing could stop him.

Hoad began by beating Rosewall, 7-5 in the fourth, in the final of the Australian Championships to set up the sixtieth anniversary we are celebrating this year. Then, in the final of the French at Roland Garros, Lew dismissed the tall Swede Sven Davidson 6-4, 8-6, 6-3 with a performance that was more remarkable than it appeared. But more of that later. It required another four sets to subdue Rosewall in the Wimbledon final and it was no surprise for Lew to find himself facing Ken once again in the final of the US Championships at Forest Hills.

Everyone knew that Don Budge had done the Grand Slam in 1938 and that nobody had done it since but the hype was somewhat less then than it would be today and one wonders just how much it played on Hoad’s mind as he walked out onto the stadium at Forest Hills. He never talked about it much because analyzing his wins and losses was never a favourite topic for this unpretentious man but he needed to be on his toes against an opponent who knew his game inside out – and he wasn’t. Despite winning the first set 6-4, which put him just two sets away from history, Lew was suddenly forced back on his heels as Rosewall’s pinpoint stroke play, mingling lobs with arrow-like passing shots, seized the match from his grasp. The last three sets were over in a flash, 6-2, 6-3, 6-3. It would need another Australian who had just joined the tour and was already in awe of the great Hoad, to achieve the Grand Slam and, of course, Rod Laver did it twice.

You need to be a bit of a history buff to realise how close Hoad came to being mentioned in the same breath as Budge and Laver and one can only speculate how it would have changed Lew’s career. As a person, it would not have altered him one iota but it might have added a few dollars to the $125,000 contract that he signed with Jack Kramer just over a year later and it might have made opponents a little bit more in awe of him than they were already.

Not just because of what he could do with a tennis racket, which was just about anything, but because of the lifestyle he led in between blasting them off court. OK, it was a different era and everyone, especially the Aussies, had a beer or two (or three if Davis Cup captain Harry Hopman wasn’t around) but Hoad was in a class of his own.

The happenings on the eve of that French final against Davidson were an obvious highlight. On the Saturday evening, Hoad and Ashley Cooper finished a late semi-final doubles victory and Lew took Jenny off to a restaurant that was still serving food. A group of Russian diplomats was sitting opposite and they fell into conversation. Toasts were exchanged. Vodka was drunk. And it continued to be drunk when the Aussie couple were invited back to the Russians flat for a night cap. Or two.

“When I got back to the hotel at six am and lay down on the bed, the ceiling was going round in circles,” Lew told me. “So I thought, bugger this and got up, put a track suit on and ran to Roland Garros.”

As one does. I am not sure where their hotel was but the distance would have covered several miles. The place was locked when he got there so he jogged in the Bois de Boulogne for a bit and, on gaining entry, took a nap in the locker room. Shortly after he tried some breakfast but threw up. Then, spotting young Laver in the corner, he suggested a hit. “But I was seeing three balls, mate. Bloody disaster!”

Another nap; a bit of breakfast which did stay down this time; one more hit with Laver and out he went to beat Davidson, who was a very capable performer on clay, in straight sets. It was hardly a surprise when Hoad and Cooper lost the doubles final to Don Candy and Robert Perry.

Today’s generation have a tough time digesting all this but it was true and, like Roy Emerson, Lew just had the constitution of an ox. Many people rate Hoad as one of the strongest men ever to play the game and Stan Nicholes, the Olympic weightlifter who was Hopman’s Davis Cup trainer, told me one day from his Melbourne gymn that Hoad was as strong as anyone he’d ever worked it. “There wasn’t a task I asked of Lew that he couldn’t do,” said Nicholes.

That strength enabled Hoad to slice off the end of his racket handle so that he could wield it like a ping pong bat. The steel wrist could then wrap whatever kind of spin he wanted around the ball, confusing all manner of opponents. The problem was that, with such a vast array of options at his disposal, Hoady often confused himself.

“Yea, sometimes I couldn’t make up my mind which shot to use and by then it was too late!”

He would be talking at the bar of the club he and Jenny had built not far from Malaga – a club that been hewn out of a hillside with the old farmhouse being turned into the bar and restaurant. Few would have thought to build a tennis club on that sloping ground but Hoad had a vision and, just to make sure it worked, helped flatten the ground by driving a bulldozer himself.

Knowing he was ill, scores of his mates like Rosewall, Fred Stolle, Tony Trabert, Butch Buchholz, Roger Taylor, Peter McNamara and Paul McNamee, who had helped Jenny organize the event, had planned to hold a tournament for him at the club right after Wimbledon in 1994. But Lew couldn’t make it, dying of leukemia a few days before.

Laver, who always admitted that Hoad had his number for the first few years they played as pros, had got as far as Los Angeles airport on his way back from Wimbledon when he heard the news. So the Rocket got straight back on a plane and flew to Malaga to pay tribute to his hero.

Lew Hoad was many people’s hero and, if you had met him, you would understand why.

(Editor’s Note -This article appeared in the 2016 Australian Open program and is published here with permission of Tennis Australia.)

Topics: Aimé Maeght, Butch Buchholz, Fred Stolle, Jenny Hoad, Lew Hoad, Paul McNam, Peter Mcnamara, Richard Evans, Roger Federer, Roger Taylor, Rosewall, Tennis, Tennis News, Tony Trabert

10sBalls Top Stories

- Bahis Sitelerinin Deneme Bonusu Kullanım Şartları

- Deneme Bonusları ile Ücretsiz Bahis Nasıl Yapılır?

- Cazip Hoş Geldin Bonusları ile Üyelik Avantajları

- Bahis Siteleri ve İlk Üyelik Bonusu Detayları

- Yeni Üyeler İçin En Cazip Bahis Bonusu

- Deneme Bonusları İle Eğlenceli Oyun Deneyimleri

- Güvenilir Bahis Siteleri: Bonus ve Güvenlik İncelemesi

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Casibom: Yaşayan Casinolar ve Bahisler Lider Platform

- Sea Star Casino: Play Games Without Registering Online

- JETZT DEN SWEET BONANZA SLOT GRATIS DREHEN

- Азартные игры с Мостбет Казино – испытайте удачу

- Çevrimiçi en iyi yuvalar: Hizmetinizde Karavan Bet Casino

Lew Hoad Profile by Richard Evans |

Lew Hoad Profile by Richard Evans |

Lew Hoad Profile by @Ringham7 – https://t.co/PW6NxaraUX #tennis @ATPWorldTour

RT @GolfEspana: #Golf Lew Hoad Profile by Richard Evans | – 10sBalls https://t.co/4rLxyyrC7o