The Big Four by Richard Evans

The Big Four by Richard Evans

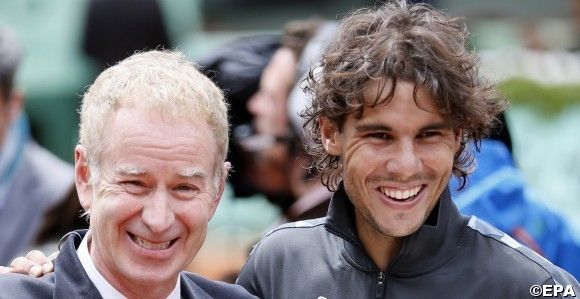

The Big Four by Richard Evansepa03259475 Rafael Nadal (R) of Spain celebrates with the trophy, next to former US tennis player John McEnroe (L), after winning his final match against Novak Djokovic of Serbia for the French Open tennis tournament at Roland Garros in Paris, France, 11 June 2012. EPA/IAN LANGSDON |

There was Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova. Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe. Stretching the field, you can talk of Rolls and Royce, Rogers and Hammerstein. But a quartet? Then, perhaps, only John Lennon, Paul McCartney; George Harrison and Ringo Starr would do.

In tennis, the Four Musketeers are the nearest equivalent but, while Henri Cochet, Jean Borotra and Renee Lacoste cleaned up singles titles at the Slams, Jacques Brugnon was only a doubles player.

So whichever way you cut it Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray are unique – unique in the annals of sport and unique in most fields of endeavor in shutting the door on rivals and doing something incredibly difficult over and over and over again.

It has been going on since 2005. Federer was up and running by then, of course, with four Slams already in his pocket but in ’05 Nadal got into the act by winning the first of four consecutive French Opens. Djokovic joined the party by winning the Australian Open in 2008 and then going on that incredible streak in 2011 which saw him collect three of the four majors that year.

Was Murray worthy of inclusion in this elite group? He settled that argument by adding the US Open and Wimbledon to his Olympic gold medal but, in fact, the Scot had been playing his part before that, acting as a sort of rear gunner to ward off the marauding hordes who were trying to break into this tight little club. After reaching the final of the US Open in 2008, Murray began a streak of 10 Slams that saw him win two, reach the final of three, the semi-final of four and the quarter final once.

As his peers in the locker room kept on repeating, “If Andy had been playing in another era, he would have won so many more Slams.”

That is the luck of the draw, of course, but as the last decade drew to a close everyone was starting to realize that something very special was happening in men’s tennis – an era of heightened achievement; incredible skill level and amazing endurance propelled by four guys who kept pushing the bar higher and higher. But if one word stood out it was ‘Consistency’.

That was the word most quoted by the frustrated pack of fine players like David Ferrer, Jo Wilfried Tsonga and Juan Martin del Potro who, with Marat Safin at the Australian in 2005, was the only other man to win a Slam during this period with his stunning victory over Federer at the US Open in 2009. “They do it every time,” said Ferrer. “They are always there, always ready, always winning. So strong and consistent. There is nothing to do.”

And that from a man who spilt blood trying. Not all of them were always there, of course, because Nadal with his knees and, more recently Murray with various problems resulting in back surgery, have been forced to miss Slams through injury. But, when they were absent, the other three closed ranks and almost always kept the door bolted. Incredibly, the lock has become increasingly difficult to pick. If one cuts the time frame to the last three years, 2011 to 2013, eleven of the twelve Slam finals played have involved just the Top4 with Ferrer at Roland Garros in 2013 being the only usurper.

And the domination does not simply exist at the very top. They are just as hard to beat at the next level, the ATP Masters 1000 Series, in which all the highly ranked players are required to play. Here the stats are almost as amazing – 68 of the last 79 Masters Series 1000 have been won by the Top4.

So who are they, this remarkable quartet that has seized on one of the world’s great sports and made it their plaything?

By age and accomplishment Federer is the leader with his 17 Grand Slam titles and 21 Masters Series wins. Personally, I believe the Swiss to be the greatest player of all time. I have never seen anyone play with such effortless artistry at such a consistent level. Before Federer I would have named Lew Hoad as the greatest and, if one is talking of artistry Manolo Santana, Ilie Nastase and John McEnroe are in the frame.

But they did not win as much as Federer on all surfaces against such brutally demanding opposition. Federer’s ability to get himself out of trouble on his serve by hitting aces was an awe-inspiring gift. So many times during his halcyon Wimbledon years, he would be 15-40 down and come back, not with one ace, but two…bang, bang, flying chalk…deuce. He volleyed like a dream in those early days, too and could produce sweet, stinging winners from any quarter of the court.

But, if one thing stood out, it was his movement. In contrast to Nadal, who one could call an earth player, Federer is an air player. He skims the surface of the court, putting minimum strain on his ankles, knees and back. It is this attribute that has enabled him to remain largely free of injury and achieve what I believe to be his greatest record (I suspect he may, too) which was to reach the semi-final or better in 23 consecutive Grand Slams. Talk to other players about what takes and they just shake their heads in awe.

Their reaction to what Nadal has achieved is not much different. A born clay courter under the guidance of Uncle Toni since the age of four, Nadal has kept on doing what true champions do – adapt, improve, succeed. It was a great effort for a baseline-hugging Spaniard to reach two consecutive Wimbledon finals in 2006 and 2007 and an even bigger one to beat Federer in the final of 2008, winning 9-7 in the 5th after a riveting duel that last 4hrs 48 mins.

The following year he won the Australian Open on Rebound Ace and, there, too, he had to adapt. But not as much as he did on Wimbledon’s grass. Many of his Spanish predecessors (Santana excluded) had come to Wimbledon, sniffed, played their own back court game and gone home early. Nadal was never going to accept that. He wanted the game’s most prestigious title and he was prepared to change his game to get it. He stepped in; took the ball earlier; learned the basics of the volley and, above all, improved the power of his first serve which he turned into a weapon.

It was the same in 2013 when, returning from a long lay off with more knee problems, he shocked everyone, not by winning a stream of clay court titles, but by claiming the title on hard court at Indian Wells and then, through the US summer, blasting his way to three more – at Montreal, Cincinnati and the US Open. What an achievement! The critics were agape. Again, he achieved all this by becoming more aggressive, shortening the points (good for his knees) and remaining as good in defense as ever.

By the time he got to Beijing in the fall, he reached another final on hard court only to get beaten in straight sets by Djokovic. But that became secondary to the fact that Rafa, by reaching the final, had regained the world No 1 ranking. It was a comeback to go down in the annals of the game.

With two semi-finals and a runners-up spot at the US Open, Djokovic was knocking on the door in 2007 and grabbed his first Slam in Australia the following year. But he was struggling with health problems that seemed to affect his breathing in extreme heat and he did not always endure himself to his public outside Serbia with macho, breast-beating demonstrations when victory came his way.

However, aided by a gluten-free diet and hours of obsessive hard work on the practice court under the expert eye of his long time coach Marion Vajda, Djokovic not only matured as a player but as a man. Opponents started to despair as they tried to find a weakness in his game. No wonder, because there really weren’t any. Only Nadal covered the back court as well as this rangy athlete who could split and hit as he extended his legs to retrieve wide balls and, slowly, his offense became more effective. And there was no better returner of serve in the game.

Everything came together for Novak in 2011 when he set off by winning the Australian again and proceeded to win his first 41 matches while cleaning up seven titles. Invincible was not too strong a word. Federer broke the streak in the semi-final at Roland Garros but Djokovic reacted by winning Wimbledon – the fulfillment of a long cherished ambition that cemented his place as Serbia’s all time sporting hero.

During these later years, Djokovic had become an eloquent spokesman for his sport and his country with his perfect English and Italian, reacting to both victory and defeat with grace and honesty.

Djokovic certainly carried the weight of national expectation on his shoulders but even he would admit the burden was not quite as onerous as that borne by Murray. As soon as the talented young Scot became a contender, he was never allowed to forget that no British man had won Wimbledon since Fred Perry in 1936. By reaching four Grand Slam finals and losing every one almost made it worse for Murray because critics started labeling him a loser (win six matches and you are a loser!) and the weight on his shoulders grew heavier year by year, even as he was winning his share of Masters 1000 titles and rising to No 3 in the world.

But Murray’s all round game, based on canny court craft as much as any particular shot, kept him right up there and when he produced his master stroke – hiring Ivan Lendl, an untested coach, as his mentor – the tetchy temperament started to fade and, after reaching the Wimbledon final of 2012, the first real breakthrough came with that Olympic gold on the Centre Court a few weeks later.

One piece of unwanted history was dispensed with when he outlasted Djokovic over five tortuous sets to win the US Open that summer and then, of course, the final, crowning glory that left him in tears with relief and joy at Wimbledon 2013 when he erased 77 years of expectation and gave Britain a new Wimbledon champion.

Djokovic, who had lost to him 6-4, 7-5, 6-4, sportingly said he did not know how Andy had survived the pressure he was under to deliver on what had become a national obsession.

But Murray’s achievement only highlighted what most people now accept – that all four of these incredible athletes are imbued with a strength of character that enables them to achieve incredible things.

Collectively and individually, they have given tennis a golden age.

Topics: 10sballs, Andy Murray, Atp, Australian Open, Bjorn Borg, Chris Evert, David Ferrer, French Open, Jo Wilfried Tsonga, John Mcenroe, Martina Navratilova, Novak Djokovic, Rafael Nadal, Roger Federer, Sports, Tennis, Tennis News, US Open, Wimbledon

10sBalls Top Stories

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Casibom: Yaşayan Casinolar ve Bahisler Lider Platform

- Sea Star Casino: Play Games Without Registering Online

- JETZT DEN SWEET BONANZA SLOT GRATIS DREHEN

- Азартные игры с Мостбет Казино – испытайте удачу

- Çevrimiçi en iyi yuvalar: Hizmetinizde Karavan Bet Casino

- Top No Deposit Free Spins Offer for Canadians – December 2024

- Abe Bet Casino: Ücretsiz dönüşlerle heyecan hissedin

- Ünlü slotlar çevrimiçi kumarhanelerde başarı bet giriş ücretli formatta

- BasariBet Casino Giriş – En Güzel Canlı Casino Oyunlarına Katılın

- Игра на деньги в казино 1вин казино: безопасность

- De parking de credits sans oublier les Diction Casino Archive sauf que Perception

- Играть в хитовые слоты в надежных клубах azino777