Pancho Segura by Richard Evans

We were having a beer late one evening at the bar of Lew Hoad’s Campo de Tenis near Mijas on the Costa del Sol. The man himself, a little heavier than in his hey-day but still handsome with his full head of blond hair, was talking tennis as he liked to do in his insightful, low key way.

We were having a beer late one evening at the bar of Lew Hoad’s Campo de Tenis near Mijas on the Costa del Sol. The man himself, a little heavier than in his hey-day but still handsome with his full head of blond hair, was talking tennis as he liked to do in his insightful, low key way.

If you asked questions of Hoadie you got straight answers with no bullshit. So one popped into my head and I asked, “What was the toughest shot you ever had to handle on a tennis court?”

Hoad didn’t stop to think. “Segoo’s two handed forehand,” he shot back. “Bloody unbelievable stroke.”

Segoo. The unique Pancho Segura, the freak from Guayaquil, Ecuador. Don’t take offense at my calling him a freak. It is how he describes himself. “I am a freak,” he says. “I was born with a hernia and malaria. Then I got rickets and they said I would never walk. I have bandy legs and didn’t learn too much at school. But I have a brain!”

I must admit to having been shocked when I first set eyes on Segura. He was playing at Wembley’s Indoor Arena in north London in one of those Jack Kramer promotions that used to draw a 9,000 capacity crowd to see most of the world’s best tennis players – Frank Sedgman, Pancho Gonzalez, Lew Hoad, Ken Rosewall, Tony Trabert, Ashley Cooper and others who had signed professional forms with Kramer and, as a result, were banned from all the world’s great championships.

Segura was on court when I arrived, maybe playing Mike Davies, the former British No 1 who had just signed up with Jack, beginning a professional career in the game that would see him go on to run World Championship Tennis for Lamar Hunt. I looked and I stared. I saw this little guy, swatting the ball with two hands on both flanks and running around like a rabbit on legs that looked no stronger than two broken match sticks. “He’ll never finish the match,” I thought. Wrong.

Segura would play thousands of matches in his extraordinary career, including a head-to-head series against Kramer himself. The promoter was still a player in the early days – he won Wimbledon in 1947 – and was considered the best of the group. Segura played Jack 85 times and ended up with a 58-27 losing record. Nothing to be ashamed of when you consider the other Pancho, the great Gonzalez could do no better than 96-27 when he played the boss.

If Segura had not needed to turn pro so early in his career, heaven knows how well he might have done at Wimbledon and Forest Hills and the other great tournaments around the world. As it was, Segoo had to content himself with winning the US Pro title three times on three different surfaces – a great feat and a strangely prophetic one because Jimmy Connors would do something very similar. And Segura became Connors’ coach. Jimmy went on to win the US Open on three surfaces – grass and clay at Forest Hills and on hard court when the championships were moved to Flushing Meadows.

Segura credits Gardnar Mulloy, a four time winner of the US National doubles with Billy Talbert, as the man who gave him a route out of poverty in Guayaquil. Pancho had been winning all sports of junior titles in South America and Mulloy, who was a youthful tennis coach at the University of Miami, gave him a scholarship. The scrawny little kid arrived just before World War 11 and made an immediate impact. Borrowing Mulloy’s partner at the US National doubles in 1944, he and Talbert reached the final.

Although not always winning, he was always giving the top stars of the day a tough time and, partially as a result of his undying enthusiasm and crowd-pleasing personality, Kramer soon signed him up when he and Bobby Riggs got the new pro circuit under way in the late forties.

Did I say enthusiasm? It doesn’t quite do justice to Segoo’s attitude towards tennis. He lived, breathed and dreamt about the game. I remember Tony Trabert telling me how the Kramer troupe would return to Los Angeles worn out after weeks on the road, having driven all over America to play one night stands in any kind of arena they could find. “We’d be pretty happy to throw the rackets in the cupboard and take a rest,” said Trabert. “But the morning after we all got back, the phone would ring and it would be Segoo. ‘Want a hit, keed?’ The guy was irrepressible.”

He was pretty irrepressible off court, too. A night on the town was an adventure with this little lothario who always had an eye for the girls. We were at the Daisy on Rodeo Drive – then the hot spot in Berverly Hills – when he spotted the blonde and beautiful wife of a very famous singer talking alone with some friends at a nearby table. Turning to me, he urged, “Go chat her up, keed. She’ll fancy you. I swear – she’s a goer!”

Luckily I had to good sense not to take his advice. Otherwise I might have ended up dead in the parking lot.

Open tennis came too late for Segura in 1968. He returned to play at Wimbledon but those little legs did not move quite as fast any more and it was inevitable that he move into coaching. When Connors’ mother asked him to start working with her fiery and talented son, Segura jumped at the chance and was at Jimmy’s side for many years instilling the young man with all the tactical nous he needed to go with that combative spirit.

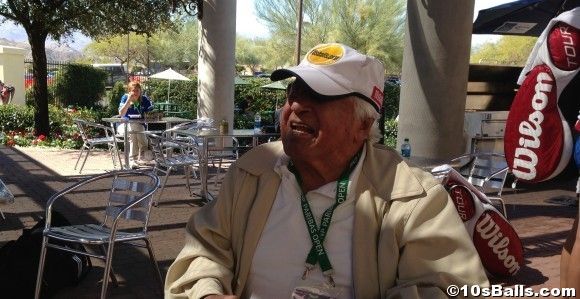

Now Segura is a living example of how a passion for something, be it sport, music, art or anything that activates the brain, can keep you young. The legs don’t work any more, which is hardly surprising considering the mileage he got out of a pair that weren’t supposed to work to start with, but the mind is as sharp as his cross court forehand used to be.

Under the care of his son Spencer or long time friend Lorne Kuhle, Segoo turns up at Wimbledon, Flushing Meadows or Indian Wells to hold court with his admirers, offering shrewd insight into the modern day players he still follows with an eagle eye. And he still loves to shock the ladies with a risqué joke.

And if you think it was just Lew Hoad who thought that double handed forehand was a unique and lethal weapon, listen to Jack Kramer. “It was the best,” said Jack. “He disguised it so well; he produced so many angles and he was so fast into the shot. It was terrific.”

And at 91, Pancho Segura is still pretty terrific, too.

Topics: BNP Paribas Indian Wells, Bobby Riggs, Campo de Tenis near Mijas, Frank Sedgman, Gardnar Mulloy, Jack Kramer, Jimmy Connors, Lew Hoad, Pancho Gonzales, Pancho Gonzalez, Pancho Segura, Richard Evans, Tennis News

10sBalls Top Stories

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Casibom: Yaşayan Casinolar ve Bahisler Lider Platform

- Sea Star Casino: Play Games Without Registering Online

- JETZT DEN SWEET BONANZA SLOT GRATIS DREHEN

- Азартные игры с Мостбет Казино – испытайте удачу

- Çevrimiçi en iyi yuvalar: Hizmetinizde Karavan Bet Casino

- Top No Deposit Free Spins Offer for Canadians – December 2024

- Abe Bet Casino: Ücretsiz dönüşlerle heyecan hissedin

- Ünlü slotlar çevrimiçi kumarhanelerde başarı bet giriş ücretli formatta

- BasariBet Casino Giriş – En Güzel Canlı Casino Oyunlarına Katılın

- Игра на деньги в казино 1вин казино: безопасность

- De parking de credits sans oublier les Diction Casino Archive sauf que Perception

- Играть в хитовые слоты в надежных клубах azino777

Pancho Segura by Richard Evans |

Pancho Segura by Richard Evans |