The Raging Bull of Tennis

Author: Jack Neworth

(Original Story in:

http://www.smdp.com/Articles-c-2011-09-01-72479.113116-The-raging-bull-of-tennis.html)

The orginal story appeared on Sept. 02, in the Santa Monica Daily Press and was wrtten by Jack Neworth.

When I was 11, my Aunt Amelia took me to see Pancho Gonzales play at the L.A. Tennis Club. I spent a lot of time with my free-spirited aunt who was divorced and childless. One thing was for sure, Amelia liked men and they liked her.

When I was 11, my Aunt Amelia took me to see Pancho Gonzales play at the L.A. Tennis Club. I spent a lot of time with my free-spirited aunt who was divorced and childless. One thing was for sure, Amelia liked men and they liked her.

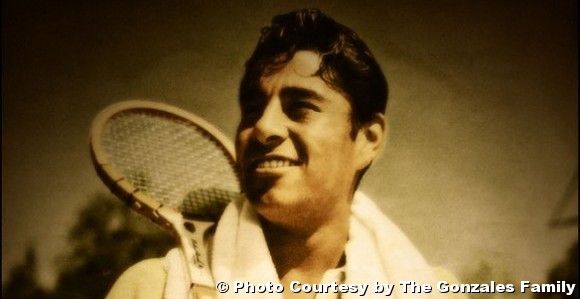

My aunt had a major crush on Pancho. Then again, most women did. He was 6 foot 3, movie-star handsome and had an explosive temper that made you watch him. As Jimmy Connors said, “It was like staring into the flame of a fire.” Powerful and cat-quick, Pancho was a fierce competitor who seemingly would rather die than lose.

In those days tennis was a country club sport and the players were exceedingly genteel. Pancho was hardly genteel. As Pancho Segura put it, “Pancho was very even tempered. Always mad.”

The oldest of seven children to immigrant parents, Ricardo Alonso Gonzales was born in Los Angeles in 1928. He was nicknamed “Pancho,” a derogatory name often given to Mexican-Americans. But around the house he was always called Richard.Gonzales grew up near the L.A. Coliseum, worlds away from country clubs. At 12, his mother bought him a 50-cent tennis racket. (He had hoped for a bike.) One day Pancho walked to the public courts at Exposition Park and the rest is history.

An incredible natural athlete, Pancho taught himself to play and, remarkably, within a few years he was winning junior tournaments. But trouble and Pancho were never far apart.

Pancho’s passion for tennis fueled his disinterest in school. His truancy violated Southern California Tennis Association rules and he was banned from tournaments. Then, at 15, he was arrested for burglary and spent a year in reform school (followed by a stint in the Navy, which ended with a dishonorable discharge).

Returning to L.A., Pancho dedicated himself to tennis, developing an overpowering 120-mph serve and exquisitely deft volleys. His progress was so remarkable that, in 1948, and as the last seed, Pancho shocked the tennis world by winning the U.S. Championship (now the U.S. Open).

The tennis community regarded Pancho’s victory as a fluke. This only set the stage for the 1949 finals where Pancho met the heavily favored Ted Schroeder. In one of the greatest matches in U.S. Open history, Pancho rallied from two sets to love to win the championship and, for the second year in a row, was the number one amateur in the country.

Married to his childhood sweetheart, and with a baby, Pancho, 21, signed a $50,000-a-year contract and joined the pro tour. But this barred him from the glamorous amateur events such as Wimbledon (until 1968 and the “Open era”).

While a rookie, he struggled against reigning champ Jack Kramer. Gonzales eventually became the top tennis player in the world for an unprecedented eight straight years. (And in the top 10 for 21 years.) His career spanned a remarkable quarter-century.

In 1968, at 40, Pancho reached the semi-finals of the French Open and the quarter-finals of the U.S. Open. Three years later, he won the L.A. Open beating a 19-year-old Jimmy Connors. The next year he won his last ATP tournament, three months shy of his 44th birthday (still a men’s tennis record).

Richard Alonso Gonzales was a charismatic icon and also a brooding lone wolf. An inner city kid, he took tennis from behind country club walls and brought it out onto the streets, defying everyone and everything: parents, opponents, sponsors and even age.

One battle Pancho couldn’t win was against cancer. In 1995 he died at age 67. Ever tempestuous, Gonzales had been married six times. (Kramer joked, “He never got along with his ex-wives, but that didn’t stop him from marrying.”) Pancho left eight children, ranging in age from 7 to 46.

Where does Pancho rank in tennis history? Dr. Allen Fox, a renowned sports psychologist, former NCAA champion and three-time Davis Cup winner, considers Gonzales the greatest player of all-time. But perhaps a 1950s star, Santa Monica’s Gussie Moran, described Pancho best, “Watching Gonzales was like seeing a God patrolling his personal heaven.”

Tomorrow evening, Pancho will finally be enshrined into the U.S. Open’s Court of Champions. (A high school dropout, he’s being “presented” by U.S. Sen. Robert Menendez, D-NJ). My late Aunt Amelia would have been thrilled. Actually, if she’d gotten her wish, this column might have been about my late Uncle Pancho.

To learn more about Pancho Gonzales go to www.Highergroundentertainment.net. Allen Fox is at www.allenfoxtennis.net. Jack can be reached at Jnsmdp@aol.com.

Courtesy Story By: Jack Neworth

10sBalls Top Stories

- Best WhiteLabel Esports Gaming Providers in Asia

- White-label Casino Platforms for Startups in Southeast Asia

- White-Label Online Casino Platform with Live Dealer Games in Asia: A Rising Trend in iGaming

- Reliable White-Label Sportsbook News Platforms in Asia

- Bahis Sitelerinin Deneme Bonusu Kullanım Şartları

- Deneme Bonusları ile Ücretsiz Bahis Nasıl Yapılır?

- Cazip Hoş Geldin Bonusları ile Üyelik Avantajları

- Bahis Siteleri ve İlk Üyelik Bonusu Detayları

- Yeni Üyeler İçin En Cazip Bahis Bonusu

- Deneme Bonusları İle Eğlenceli Oyun Deneyimleri

- Güvenilir Bahis Siteleri: Bonus ve Güvenlik İncelemesi

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Reasons Behind the Increase in Sex Shops

- Casibom: Yaşayan Casinolar ve Bahisler Lider Platform

The Raging Bull of Tennis

The Raging Bull of Tennis